Egg Interview December / January 1990

Big thank you to Tiffany for taking the time to write this one

down for me and for scanning the pictures Big thank you to Tiffany for taking the time to write this one

down for me and for scanning the pictures

By Diana Rico

Photographs by Jeffery Newbury

A little fright music

Composer Danny Elfman created the creepy music for Batman, Beetlejuice,

Dick Tracy, and those holy terrors The Simpsons, so damned if he's scored

to death doing the sound track to Edward Scissorhands.

Danny Elfman has scored 15 films in 5 years. Not bad for someone whom

director Tim Burton was told not to hire because he was utterly untrained

as a film composer. Evidently, Burton knew it depends on what you mean by

training. No, Elfman did not go to the Boston Conservatory. But he did spend

his youth in postwar suburban Los Angeles worshipping horror and fantasy

films at a temple known as the Baldwin Theatre. He's been a fan of Bernard

Herrmann and Nino Rota since before he joined his brother's musical-theatrical

troupe Mystic knights of the Oingo Boingo, which in 1978 became the cult

fave rock band Oingo Boingo.

Burton must have assumed those were pretty solid credentials for Pee-wee's

Big Adventure. Elfman's loony, antic score helped make Pee-wee a surprise

hit, and a collaboration was born. Beetlejuice, with it's Harry

Belafonte-meets-The Haunting sound track, was the second joint effort, and

the ultimate smash Batman, with it's brooding, mystic, melancholic heroic

themes, was the third (no it wasn't Prince who wrote the good stuff).

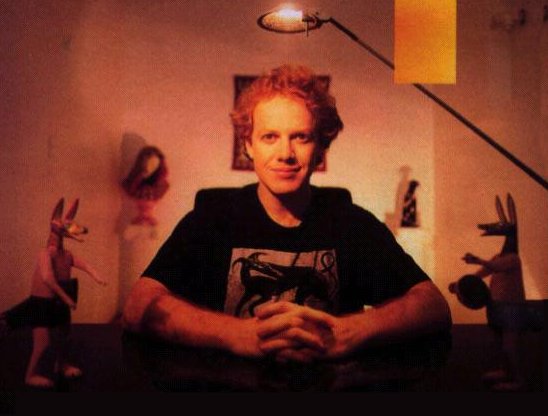

An admitted workaholic, the devilish-browed, fiery-haired composer

has, at 37, created the music for films as wide-ranging as Midnight Run,

Nightbreed, Darkman, and Dick Tracy (no, it wasn't Madonna who wrote the

good stuff), as well as the theme for The Simpsons, while putting in a

hyperactive schedule of touring, songwriting and producing for Oingo Boingo.

Now Burton and Elfman have collaborated again for Christmas. Edward

Scissorhands (Fox) is a gentle fairy tale about a pale, raven-haired

boy-creature, Johnny Depp, who, because of the accidental death of his inventor

(played by Burton's childhood hero Vincent Price), goes through life with

slashing blades for appendages. Elfman thinks this is sweet, but then, this

is a man whose aerie in the Santa Monica Mountains, which he shares with

his wife, two daughters, and various dogs and cats, boasts an enormous collection

of third-world folk objects, most of them centering around death. His downtown

L.A. loft is cluttered with African and Indonesian instruments; long, gossamer

drapes float eerily in the breeze. Burton and Elfman usually seem to be competing

to see who can wear black more often in L.A. at high noon. The two men are

going to be partners a long, long time.

[We're in Elfman's home.]

Diana: Is this Mexican Day of the Dead stuff?

Danny: It's from all over- Africa, Indonesia, Peru. This here is one

of my prize objects. [opens an ornate box.]

Is that a shrunken hand?

A shrunken monkey hand. Each finger is for a different incantation.

I got it in west Africa. [in the jolly tone of a kid showing you his baseball

cards:] This one's a real Ecuadoran shrunken head. It's my latest addition.

Do you ever worry that your collection might have negative energy?

No. I have enormous respect for African juju. I don't fear the objects,

like in a movie- horrible spirits getting up in the middle of the night to

do me harm. Besides, I've had many of these 10, 20 years, and I've not exactly

had the worst luck. In fact [laughs], maybe...

They've helped your career? Film Scoring's an odd kind of creative

endeavor: You're writing music for a predetermined time frame, to fit images

that are edited together a certain way. What happens if you've written a

melody that should climax at a certain point, but the Batmobile's supposed

to slam into the wall three beats later?

There are two things about being a film composer. The art comes from

my soul. The craft concerns the fact that you don't control the timing of

the scene, and you have to adapt what you feel is this wonderful artistic

expression to the medium in which you are working.

What got you interested in it?

As a kid I would see movies five, six, seven times if I liked them,

and I learned early on that a lot of my favorite 50's and 60's fantasy films

had wonderful music by Bernard Herrmann. Journey to the Center of the Earth,

The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, Jason and the

Argonauts, Mysterious Island- these were just great, and the two things I

always loved were Ray Harryhausen's animation and Bernard Herrmann's music.

Especially his score for The Day the Earth Stood Still. It was the first

time I was moved by music, the first time I realized how it made the story

and characters seem important. Later, as a teenager, I went from being a

movie fan to a [in a mock-serious voice:] Cinema Fan. I would go out at least

three nights a week, see every Truffant, every Fellini- Nino Rota's music

[The Godfather, parts I and II, Amarcord, Fellini Satyricon, 8 1/2] became

like second nature to me- and I rediscovered Bernard Herrmann in Alfred

Hitchcock's films.

I hear a lot of Nino Rota in Pee-wee's Big Adventure.

Pee-wee was very conciously Nino Rota, and there are a couple of cues

in Darkman where I get very Bernard Herrmann-like. Paying tribute to the

masters. When I put on record at home it's very likely a Russian composer-

Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Shostakovitch- but I'll mix in Bernard Herrmann or

Nino Rota. These are kind of fightin' words, but to me it's all relevant

and valid.

You've got to realize music is the most elitist of all the arts. It's

incredible the amount of flak I draw because I'm untrained. Shirley Walker,

my conductor, is constantly being asked by other composers, "Come on, you

really write his music, don't you?" It's not weird for a director to come

out of the blue, be self-taught, and learn while doing films. But for a composer

to learn by instinct is unheard of. There are a lot of people out there who've

paid their dues for many years and can't accept that. But I paid my dues

for over a decade earning nothing in rock 'n' roll. Oingo Boingo achieved

a very intense cult audience, but never mainstream success- and it doesn't

matter. We do it because we love it.

You may have gotten a lot of press for your first few films because

you already had a name in rock.

Yeah. I think that's also why I'm so despised in the industry. You're

supposed to be more or less invisible, s-l-o-w-l-y emerge in the public eye,

a la John Williams, who's the only composer well known to the public. Jerry

Goldsmith [Chinatown, The Omen, Poltergeist, Alien] has been doing amazing

stuff, as has Ennio Morricone [Casualties of War, The Untouchables, The Mission,

Fistful of Dollars], for over a quarter of a century. But your average people

on the street have never heard of them.

But you also seem to have picked the right films.

I go mostly by filmmaker. I sought out Clive Barker and Sam Raimi

after I saw Hellraiser and Evil Dead II. Hellraiser was one of the best really

scary films I saw that year, and Evil Dead II was an absolute classic. And

though I'd work with those people again in a second, certainly Tim Burton

is my first priority. I'm excited about Edward Scissorhands. The script [by

Caroline Thompson from an idea of Burton's] is wonderful. Coming off the

hardships of Batman, Tim wanted to do something very simple and light, and

I'm in exactly the same frame of mind. It's always a very wonderful experience

working with Tim. He's so creative that he allows me to be creative.

As a kid I would see movies five, six,

seven times if I liked them, and I And the score is very

important to him. As a kid I would see movies five, six,

seven times if I liked them, and I And the score is very

important to him.

It's important to any unusual movie. Tim won't preview without it.

They tried previewing Darkman without the music, and it was an absolute disaster.

When they previewed it again with the score, people loved it.

What was it like working on Darkman?

Fun. There are long segments where you've got this poor, pathetic

Darkman character wandering through life, which lent itself to a big,

melodramatic, melodious, tragic score. Very old-fashioned. I prefer the way

movies were scored 20 or 30 years ago: bold, in your face. The score was

a much more important element then.

Now it seems sound tracks are defined by the pop songs dropped into

them for marketing purposes. People think Prince wrote the whole score to

Batman and that Madonna's "inspired by Dick Tracy" album is the sound track

to the film. I just saw The Jetsons, and all these Tiffany songs are dropped

in for no reason other than to sell Tiffany songs.

I think it's a very, very dangerous and negative trend. It's been

happening for over a decade now. Every time there is a hit song off a film,

it encourages everybody else to drop half a dozen songs into their film.

Now and then somebody will put a song in for a reason, but more often it's

bullshit.

I feel very lucky that I've had as many scores released on album as

I have. Especially Batman- releasing two albums had almost never been done

before. Jon Peters was skeptical about me at first. I'd never written an

action-adventure score, so he said, "I'm gonna ride your ass, but you'll

be glad in the end." I'd play things and he'd say, "You still haven't sold

me on Batman as a hero." I played one thing, "no." Played the next, "no."

Finally Tim whispered to me, "Play that march you played for me yesterday."

Jon got up and started conducting. And that became the theme. When we were

scoring in London, he got excited and told me, "I'm going to get you a

sound-track album, you watch." And he did. [We decide to head for Elfman's

loft. With him at the wheel of his Supra, we fight through Pacific Coast

Highway beach traffic before hitting cruising speed on the Santa Monica Freeway.]

Do you do your film work at home and your Oingo Boingo work downtown?

They cross over. I do most of my writing in my studio at home. But

I missed having a big open space to pace in- for 10 years I lived in lofts

in L.A.- so I thought, "I'm successful enough, I can treat myself to a second

space." It's about the only really extravangant thing I've done. I still

have a very difficult time believing that I'm successful at anything. [suddenly

he slumps down.] Shit! There's a cop behind me!

Is he pulling you over?

[sounding worried:] He could be.

Why? You weren't speeding.

[checking rearview mirror:] Yeah, I was.

I don't think he's pulling you over. He'd be flashing his lights.

[finally the cop pulls ahead of us.] Oh, he just wants to go faster than

you.

AAARRRGGGHH!

Don't you hate that? I instantly feel guilty if there's a cop.

Who doesn't go 60?

Who doesn't go 70? I got my last two tickets on this very stretch.

It was late at night, not going any faster than anybody else around, and

I got nailed. At two or three in the morning, going home from work, who is

ever going 55 when you're all stretched out about a city block apart?

Well, you lucked out this time.

I heard that for Dick Tracy you were writing music over the phone.

We had finished everything, I was on tour, and they decided to change

the entire opening. So they took a piece I'd written for the end of the movie

and cut it into the new beginning. I got Warren on the phone and practically

begged him to rewrite it. He said, "Do you really think you need to? Everybody's

pretty happy with it." I said yes. And Warren said, "Okay, you got it." So,

I wrote two versions in my hotel room that night, [orchestrator and Boingo

guitarist] Steve Bartek orchestrated them, we sent them to L.A., and I got

on the phone just to hear them played. But of course you know how stories

go in L.A. [Laughs.] It's already become one of those legends: "God, how

he scored it over the phone!"

[We pull into a typically grungy parking lot deep in downtown L.A.,

enter his building, and climb up a surprisingly magnificent staircase that

looks like something Audrey Hepburn posed on in Funny Face.]

What a great old building. What is it?

It's an old embassy. [we enter the enormous loft.] I haven't seen

this place in ages.

How often do you come down here?

Never. Well... Occasionally. [He walks all over, as if to imprint

himself on the space.] I have always wanted something like this. I'm going

to shred the bottoms of all these curtains. I want it to look like a haunted

house set. [he kicks back in a chaise lounge and savors the view of the

rooftops.] Ahhh, I love this spot! I'm going to start making use of it this

year.

How do you manage to do film work and keep a band together? Do

you drive yourself nuts?

[laughs.] That's it in a nutshell. But the thing that's great about

having my studio at the house is that I can see my children at dinner and

play with them for an hour. I work till two or three in the morning, and

they're up at seven and gone by eight, so that little bit of time means a

lot to me.

Do you take them to see your movies?

Before they're done. They even saw a shooting for Nightbreed, a wonderful

decapitation scene. I would have killed to see that when I was 10 or 11!

[we go into the kitchen and dig into some french fries his assistant has

brought in.]

How come you have so much death in your Oingo Boingo stuff?

My Boingo stuff? How about everything?

True. I didn't want to say

it, Danny, but... True. I didn't want to say

it, Danny, but...

My choice of movies...

Your skull collection at home...

Monsters and horror just always held this fascination for me. I never

quite got over it and became an adult. It started probably when I was 10.

I had the walls of my room covered with gore, cutouts from Famous Monsters

of Filmland. It was a monster museum.

Have you ever been to [Famous Monsters editor] Forrest J. Ackerman's

place?

Mmmm! I've been invited by a friend.

Go. He's got the little Ray Harryhausen monsters, a copy of the

robot from Metropolis- just everything that you would love.

Not to mention that he was my first idol in life. To us Forrest J.

Ackerman was God. I have to go out there this week before things heat up

again. But if you'd asked me what I wanted to do when I was a kid, it would

have been special effects in movies, makeup, maybe editing, working toward

cinematography, something like that. I would never have even guessed music.

I came full circle after all those years, right back to the medium which

inspired me in the first place, on a side of the fence that I never expected.

Would you like to make your own films someday?

Mm-hmm. I've got a number of strange tales in my head. I'm writing

a story now, hoping that someday... though that day may never come.

Then again, it may. You never thought you'd be doing the work that

you're doing now.

Exactly. That's why I know that it may. Because what I'm doing already

is a longer shot than that. |